Return on Capital Employed - the profit engine of a business

Let’s assess the profit engine of a business - the ability of a business to generate high rates of return on cash profits reinvested back into the business. We’ll do this by looking at a measure called Return on Capital Employed.

How a company grows its capital through retained profits

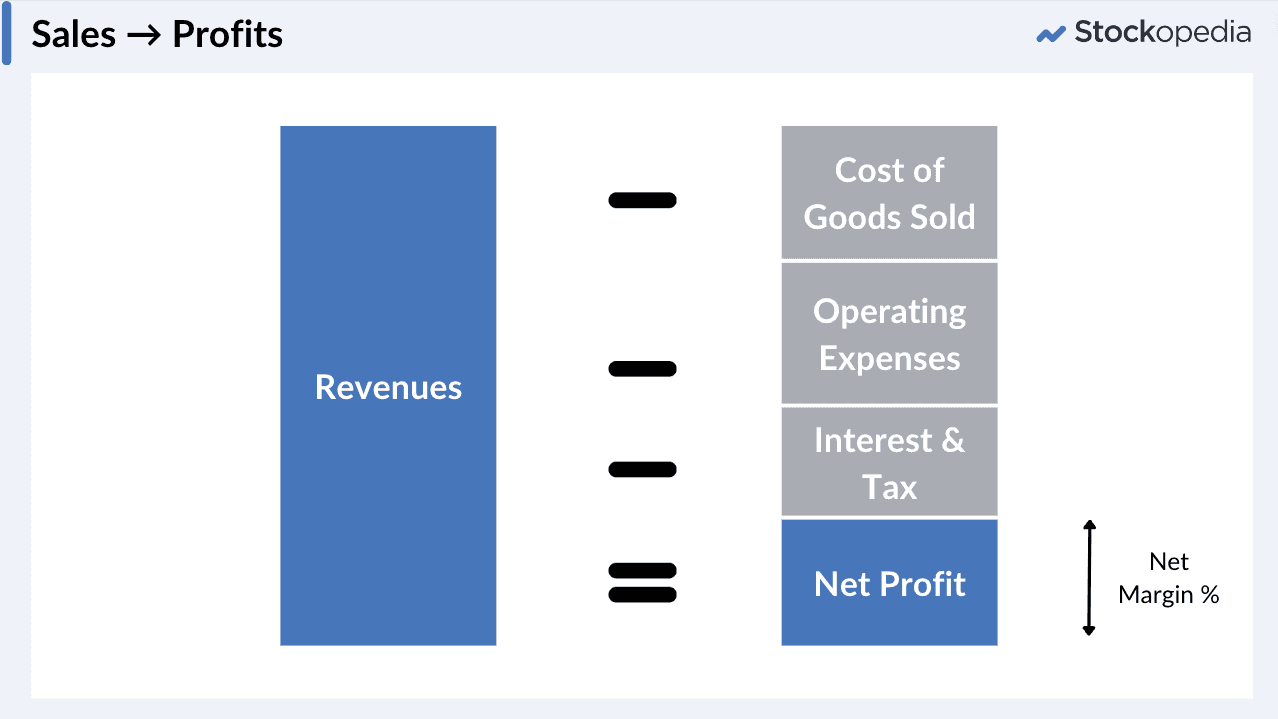

As a precursor, let’s return to our sales to profit calculations. After subtracting the Cost of Goods Sold and also the Operating Expenses, a company also needs to pay the interest owed to bond holders, and also the taxes due to the government. That leaves the Net Profit attributable to shareholders. (The Net Margin can be calculated by comparing the net profit to the revenues of the business.)

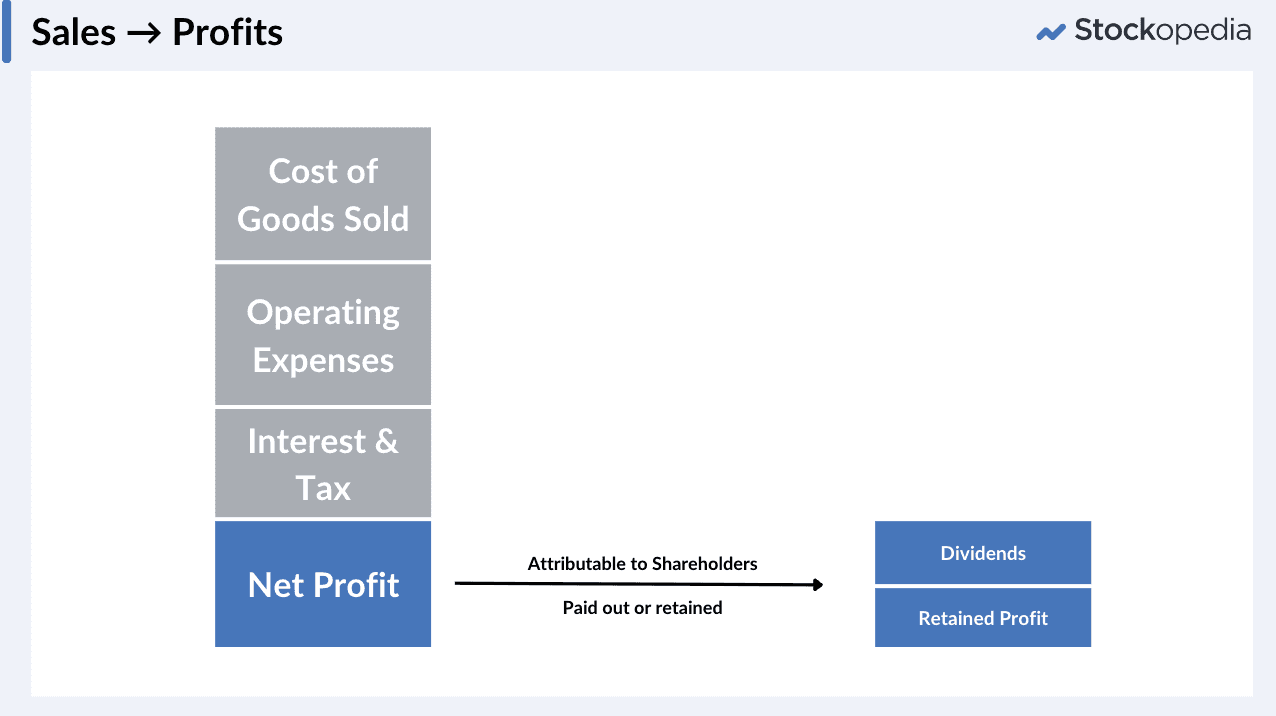

Net Profits can either be paid out as Dividends, or they can be retained by the business for reinvestment as Retained Profit.

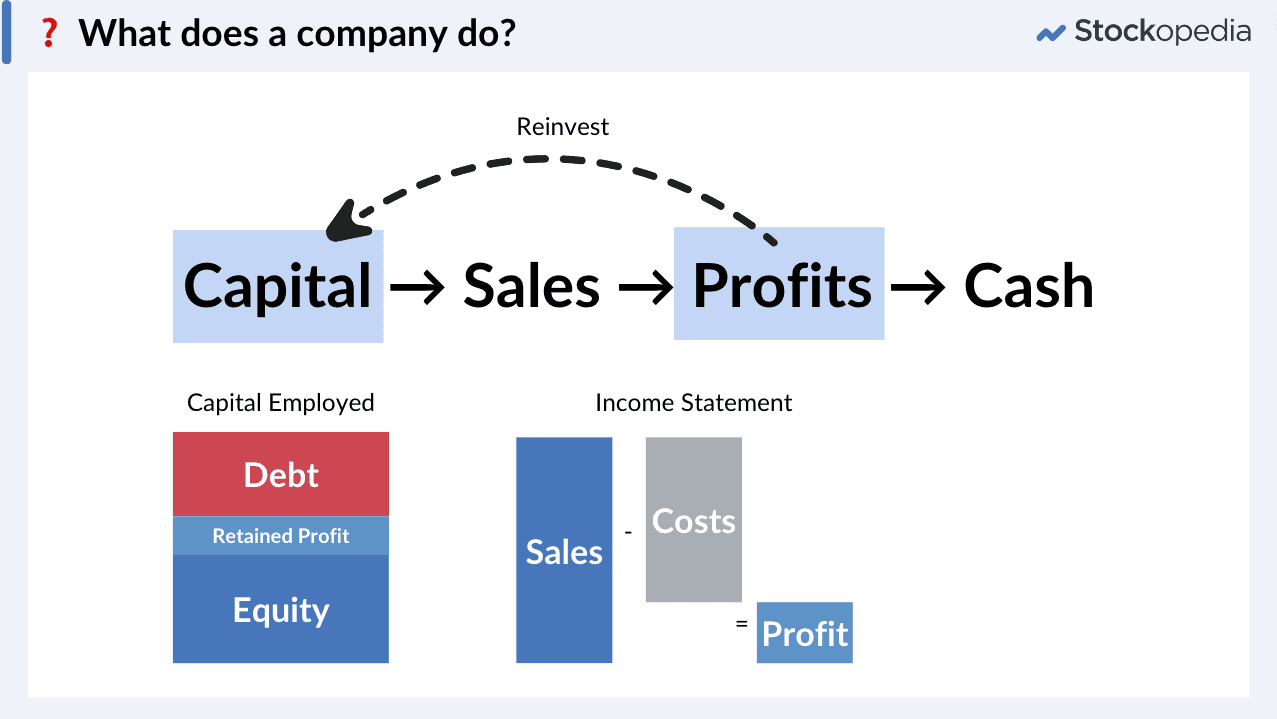

Let's imagine what's going on here from the lens of the company’s . On the balance sheet you have the Equity (shareholder funds in the business), and you've got the Debt that's been borrowed to invest in the business. That's essentially the “Capital Employed”.

If we compare the Income Statement, that reports the revenues (or sales), the costs and ultimately the profits. If the business were to keep all of that profit, it can be reinvested back into the capital of the business as retained profit. This gets registered on the balance sheet as an increase in Equity.

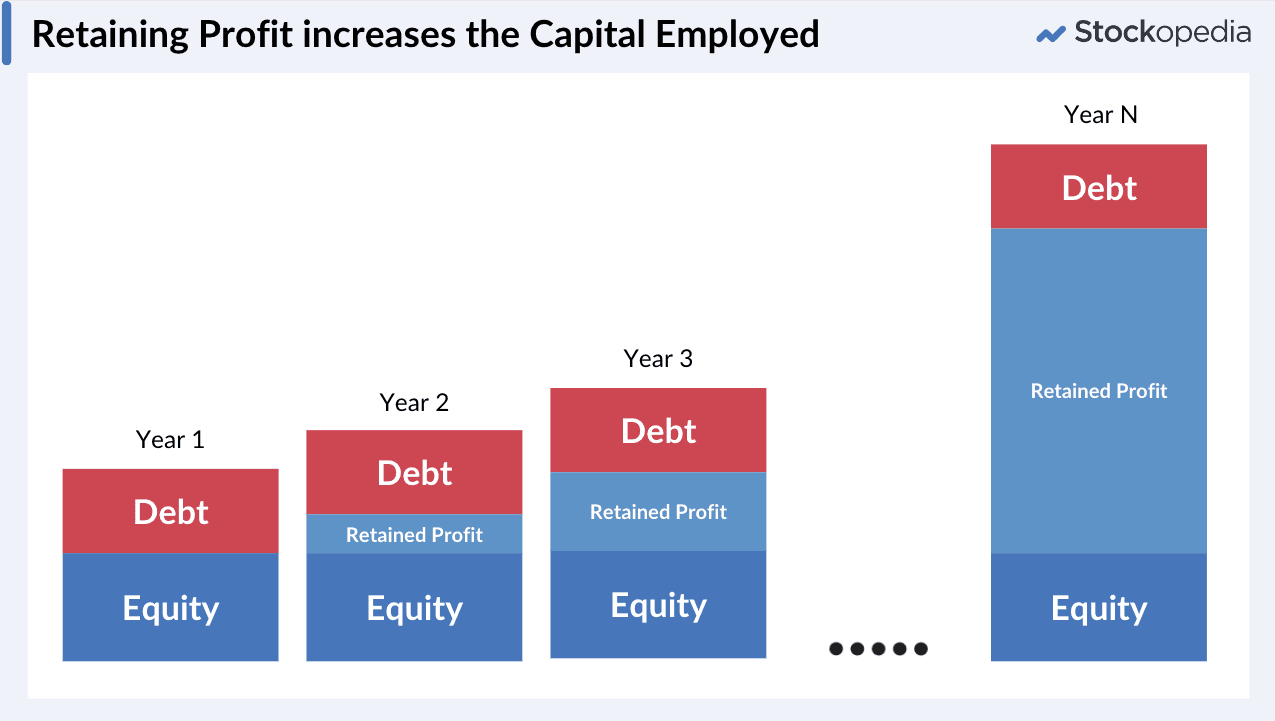

This is a powerful mechanism. Over time, on an annual basis, a company will ideally trade, create profit, retain some of that profit, and increase the capital in the business. A good business will retain more and more profit every year and keep putting it to work at high rates of return.

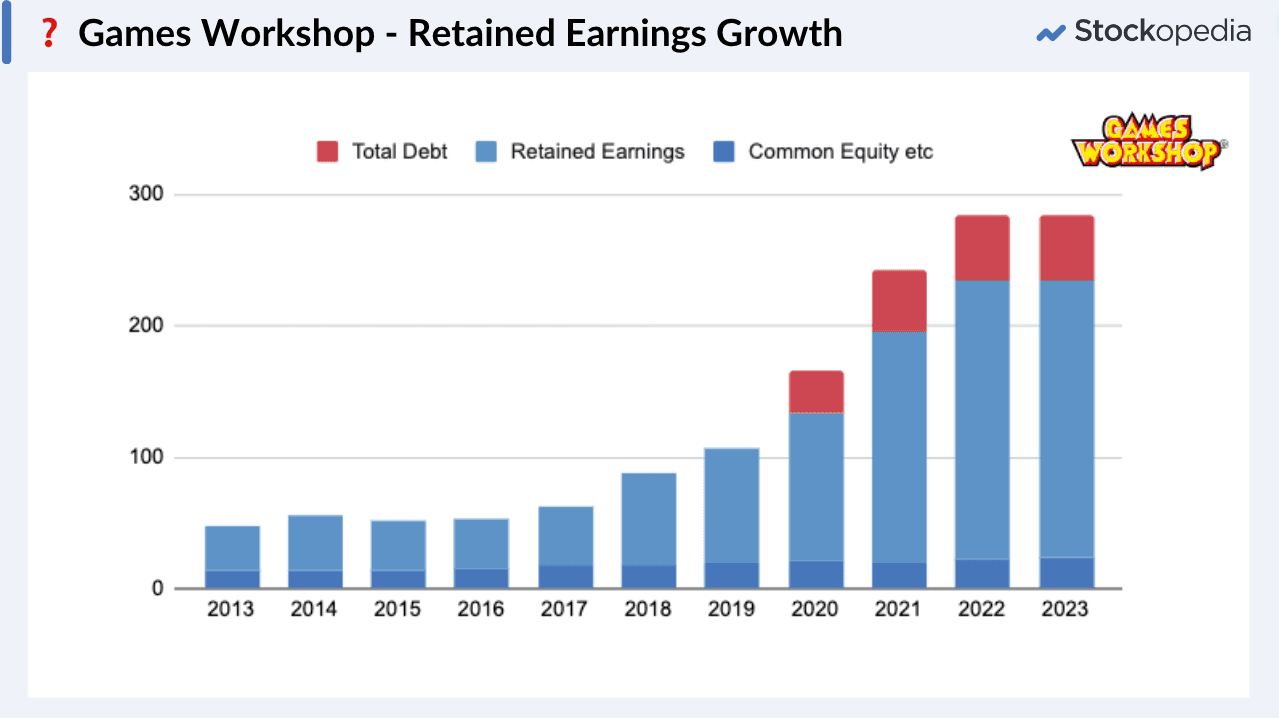

Games Workshop’s Retained Profit Growth

We can illustrate this with Games Workshop’s financial statements below. You can see that in light blue is the retained profit it, which starts growing and accelerating through time. In the later years there are some debts taken on by the business (red), albeit mostly due to changes in accounting standards on leases.

Now a key question is, can the business use that extra capital effectively? And this comes down to a simple equation which calculates the return on capital employed. So let's quickly understand this key line item.

Understanding Return on Capital Employed

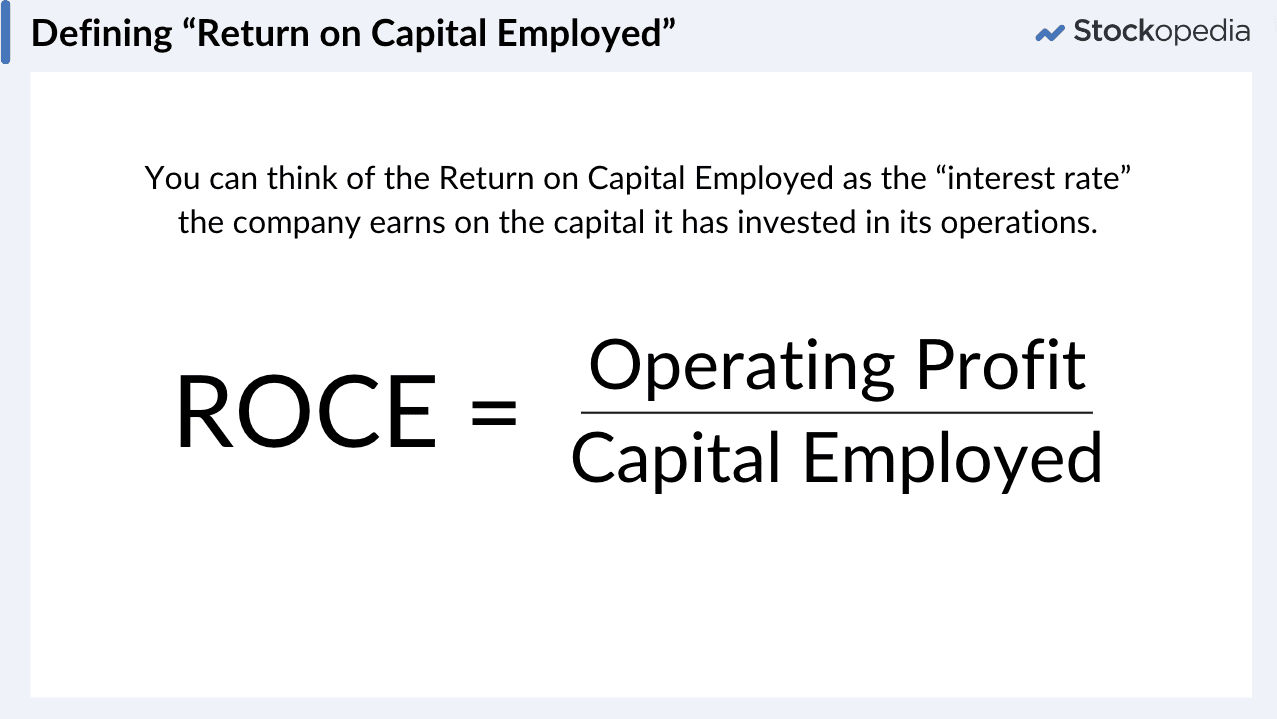

The calculation of Return on Capital Employed (abbreviated as ROCE and colloquially known as “Rocky”) is simple. It's the Operating Profit divided by the Capital Employed. You can think about this as the bang for the buck of profit versus the capital employed in the business.

Some people like to call the ROCE the “interest rate” that the company earns on its capital. So that actually gives us a little bit of an indicator because we can then compare this against the Cost of Capital.

Capital has a cost. Let's imagine you are buying a house with a mortgage. That’s borrowed money, and you’ve got to pay an interest rate on the loan. It's no different for businesses. They've got a cost of capital too, whether that capital's come from equity shareholders or it's from bondholders.

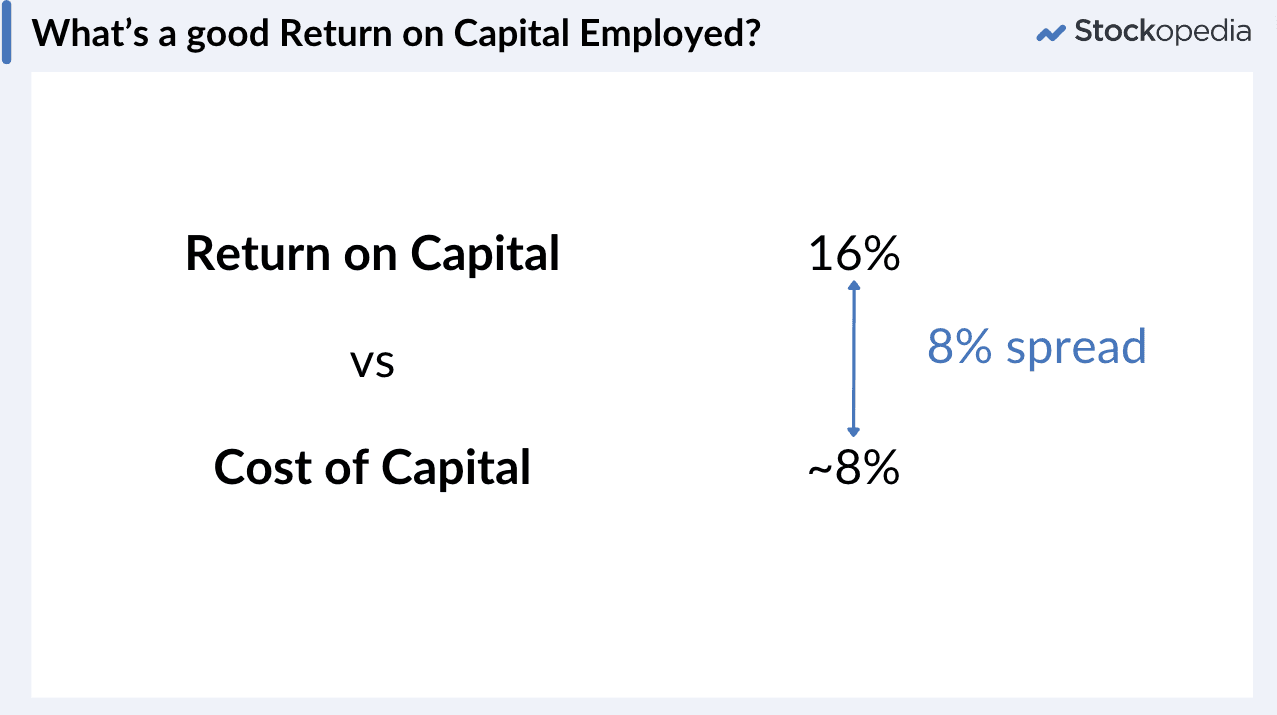

There are many ways of defining the Cost of Capital, but a good rule of thumb is to assume an 8% to 10% rate, as it’s the approximate opportunity cost for any capital invested in a business. When you're assessing the Return on Capital, you want it to be significantly higher than the cost of capital.

The cost of capital can differ for different businesses. A big, stable business might have a lower cost of capital, but a young, speculative business might have a higher cost. Ideally, a business should have a good spread between the return on capital and the cost of that capital.

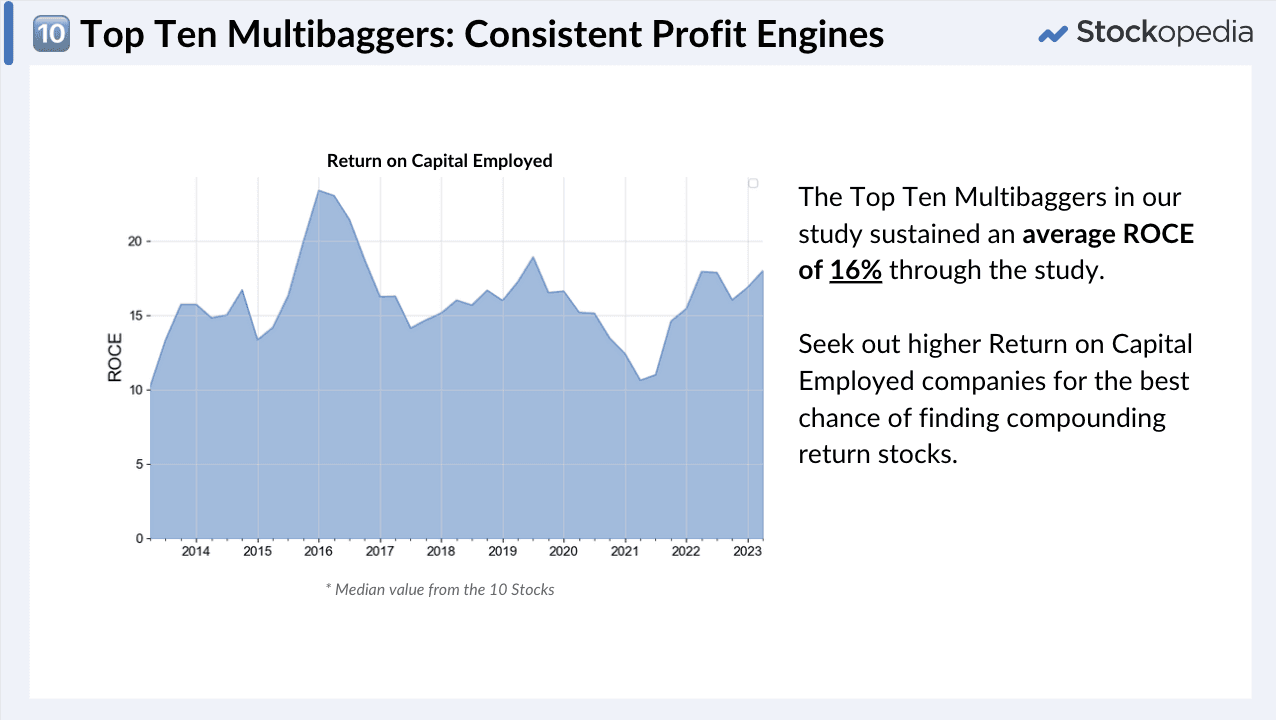

We found that the Top Ten Multibaggers of the last decade sustained a Return on Capital that averaged about 16% through the ten-year study period. The key idea is to seek out higher return on capital businesses for the best chance of finding stocks that can compound over the long run.

Is the Return on Capital sustainable?

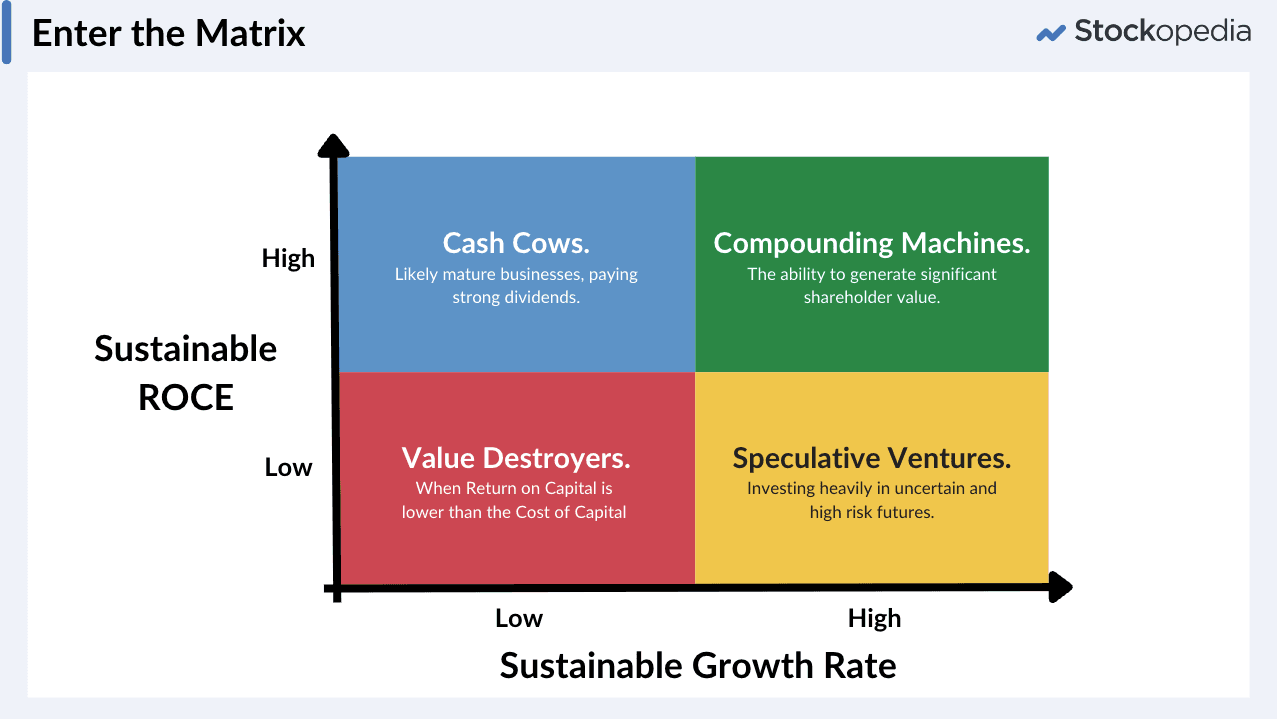

If a company is making profits, and retaining those profits, a question to ask is, can it sustain a high return on capital as the capital base grows? If it can't reinvest that capital effectively, it shouldn't be hanging on to it. It should be paying its profits out as dividends or buying back shares. The following matrix helps us understand some scenarios here.

On the horizontal axis is the growth rate of a business from low to high, and on the vertical axis, is its Return on Capital Employed.

In the top left quadrant are high return on capital, low growth companies - the

cash cows. Often very nice businesses, dividend paying for their investors, but not much promise of growth.

In the top right quadrant are high return on capital, high-growth companies - the

compounding machines. This is the dream quadrant for investors. It really can generate significant shareholder value if a company can propel itself into this quadrant.

In the bottom right quadrant are low return on capital, high-growth businesses - the

speculative ventures. These businesses are possibly investing heavily with the dream of high future returns.

In the bottom left quadrant are low return on capital, low growth businesses - the

value destroyers. You can think of businesses like General Motors and Ford and many highly capital intensive businesses, with inconsistent operating histories and a lot of debt finance.

It can be great to identify companies that may be Cash Cows or Speculative Ventures that can move and progress into the Compounding Machine segment - as those may be the great Multibaggers - but there are also steadier growth compounders, which are already at quite high valuations, which can continually grow and grow and grow.

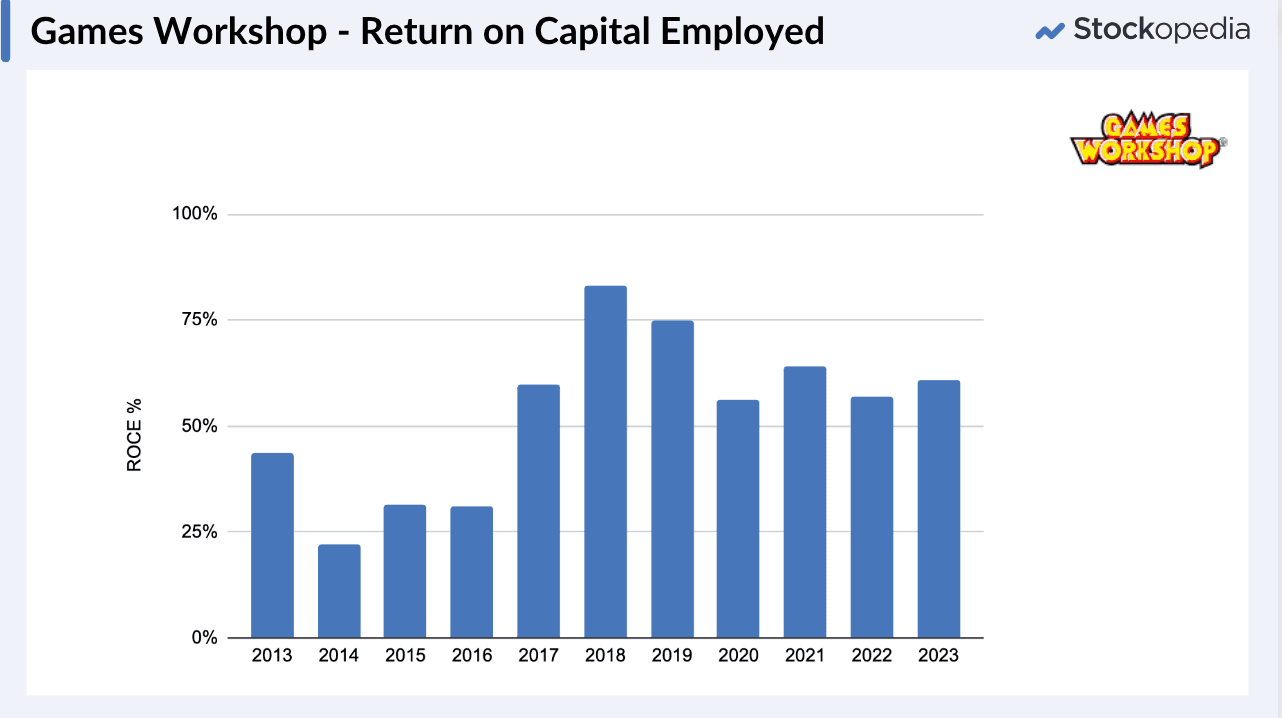

Games Workshop’s propulsion into a Compounding Machine

Games Workshop actually started its journey toward multibagging as a Cash Cow but its strategy propelled it into the top right Compounding Machine quadrant. It had an already strong return on capital (20-25%), and was highly profitable, but then its strategy started kicking in in 2017 that really gave it huge Operating Leverage. This significantly increased its return on capital to an extraordinary 60% plus. This is an indication of a strong competitive advantage.

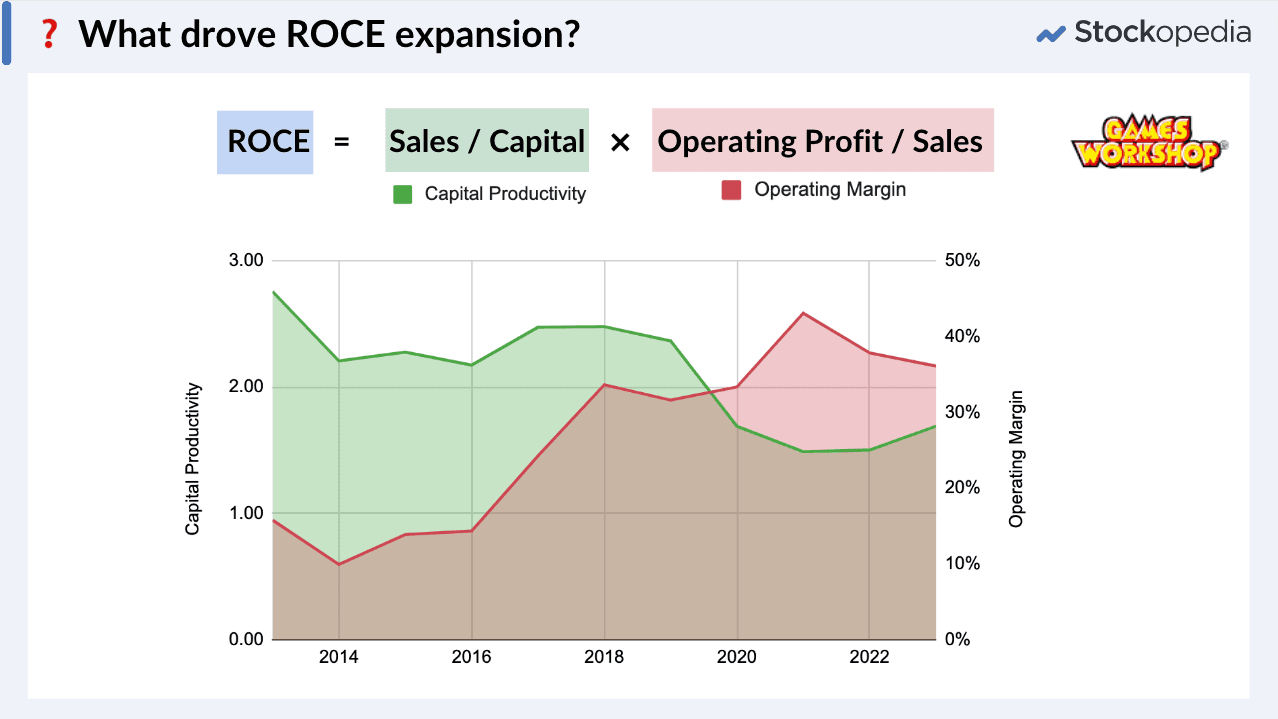

Breaking down the components of Return on Capital

So what actually drove that expansion in the return of capital? Well, you can break down the return of capital into two components - the Capital Productivity (or capital turnover), which is the amount of sales per unit of capital in the business, multiplied by the Operating Margin that we defined in the previous article.

We've already seen how the operating margin hugely expanded in Games Workshop through that growth period. But interestingly, the capital turnover or productivity declined from its peak, as the accounts started showing a larger proportion of debt.

So just to summarise this section, potential multibaggers can be driven by a high sustainable return on capital employed because that may indicate that the company can reinvest at high rates of return, and can be financial evidence of a powerful competitive advantage. But a key takeaway is that reinvested profits should not diminish the return on capital employed as the company grows.

In the next article, we’re going to talk about cashflow, as not all profits are created equally. Sales are vanity, profit is sanity and cashflow is king!